Justin is a bright, funny, creative 10-year-old boy. He loves science and reading. He builds rockets, watches movies and spends hours playing with his dogs, Rascal and Champ. He had a part in his 4th grade play, was on the winning team in his community softball league, and has traveled to Washington, DC to meet with legislators.

In addition, Justin has an intellectual disability. He also has a massive pet peeve: he hates being called “retarded.”

It turns out that Justin’s not alone in wishing that people would pay more attention to the things that he does well, rather than to his diagnosis. Folks with a variety of disabilities are speaking up and asking us to think before we speak or write about them.

In a world where a diagnostic label can easily become a playground taunt or a laugh-grabber in a movie—how often do you hear the R-word said as an endearment?—people who are assigned these labels are stigmatized, ridiculed, or worse, seen as easy targets for abuse. Throughout history, words like retard, idiot, spaz/spastic, and moron—all originally diagnostic labels—have been adopted as insults. Yes, we often use them without thinking, but we can do better.

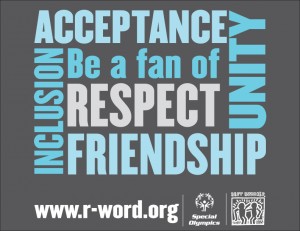

Some folks may argue that changing the language we use when we speak or write about people with disabilities is futile—that whatever we call people will become the new insult—or purely an exercise in political correctness. The points are well taken, but misguided. Those same folks would be hesitant to say the N-word out loud in a room-full of people. It isn’t about political correctness. It’s about respect, eliminating words that humiliate and ostracize whole groups of people, and shifting the cultural dialogue about disability from one of pity, fear and shame to one of inclusion.

Known as, “People First Language” the guidelines for respecting the dignity of folks with disabilities are pretty straight-forward.

First, we only refer to a diagnosis or a disability if it is relevant and critical that we do so.

Second, when we do need to talk about the diagnosis, we try to be respectful of the person, and we refer to the person first. So we would say, “man with a disability, student with a learning disability or person with an intellectual disability” rather than, “disabled man, LD student or retard.”

Let’s work together to remove diagnostic labels from our joke and insult vocabulary. It’s going to take practice to break the habit of reaching for those words, but if we gently remind one another when it happens, we’ll quickly eliminate them.

As Kathie Snow so eloquently says, “They are people: moms and dads; sons and daughters; employees and employers; friends and neighbors; students and teachers; scientists, reporters, doctors, actors, presidents, and more. People with disabilities are people, first.”

Justin sums it up perfectly when he says, “Call me Justin. That’s my name!”

This article originally appeared in Hope and Dream Magazine.

your thoughts